As social media blacked out Tuesday, June 2, 2020 – taking a poignant time out to encourage us all to think about our history and our future, our thoughts and our actions – Consociate Media’s family took time to have some heartfelt conversations.

We talked with each other.

We talked with family members.

We talked with clients and friends.

The words were all different. The experiences all different.

But the objective was the same – find a way to come together, united as one people, one community, one love.

With the power we have within the talent pool at Consociate Media, we also asked ourselves, “what can we do? What should we do? What are we capable of doing?”

The answer was clear.

Tell stories.

So today, as social media blacked out to give us all a time to reflect, we took time to visit, photograph, research and write the stories of some of the most historic landmarks in our region that speak to history. Black history. Our history.

May these stories provide some inspiration for strength, hope, love and unity. Let us not let history repeat itself. Let’s band together for change.

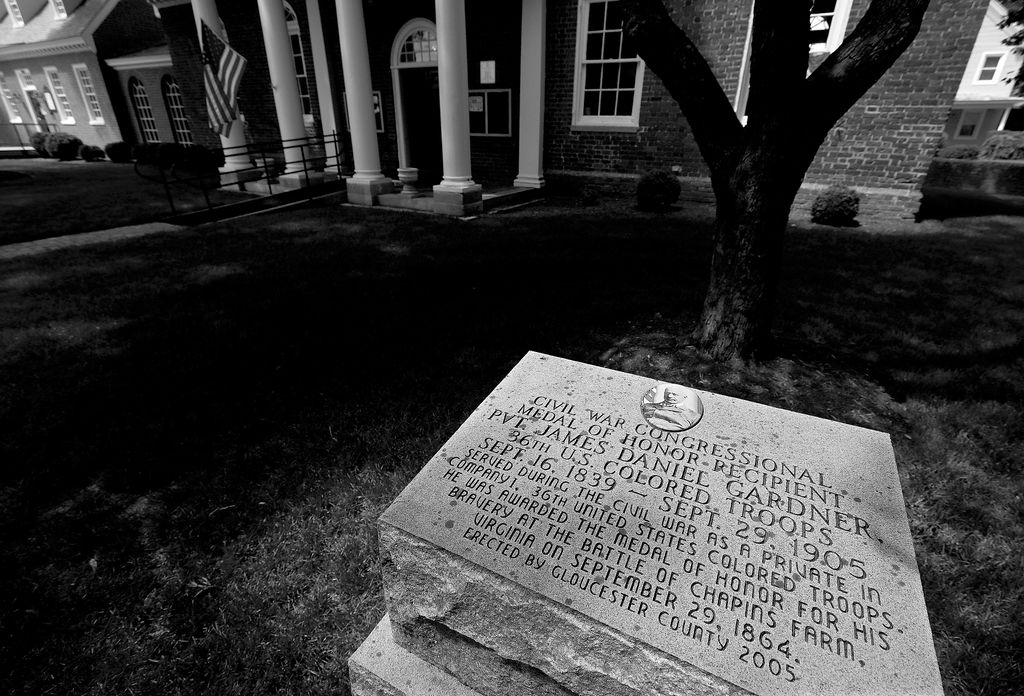

Civil War Congressional Medal of Honor Recipient Private James Daniel Gardner

Born in the time of slavery in Gloucester, Virginia, James Daniel Gardner fought in the Civil War with the 36th U.S. Colored Troops.

On Sept. 29, 1864, in the battle at Chapins Farm, Gardner “rushed in advance of his brigade, shot a rebel officer who was on the parapet rallying his men, and then ran him through with his bayonet.”

For his bravery, Gardner earned the Medal of Honor, our nation’s highest medal for valor.

In 2005, a monument honoring his bravery, his service and his work to securing the freedoms of so many, when he himself was not born a free man, was erected in the historic circle along Gloucester Main Street.

The Irene Morgan Story Begins

On an obscure and tucked away corner, just off of U.S. Route 17 and around the bend from the Consociate Media offices, there once stood the Hayes Store Post Office.

It was there, on that site, where Irene Morgan boarded a Greyhound bus on July 16, 1944. She was returning to home to Baltimore after a visit with her mother when, about 25 miles north of the post office site, the bus driver ordered her to give up her seat so that white passengers could sit. Morgan refused and was arrested and jailed in Saluda.

Her case would ultimately reach the U.S. Supreme Court, which in Morgan v. Virginia in 1946, decided that the laws requiring segregation of passengers in interstate transportation were unconstitutional.

Morgan made her stand, her history, 11 years before Rosa Parks.

Woodville School

The Woodville School in Gloucester, Virginia remains one of the last remaining Rosenwald Schools built across the south for African American children between 1912 and 1931.

Julius Rosenwald, CEO of Sears, Roebuck & Co., funded 5,300 elementary and training schools in partnership with local communities. In 1919, T.C. Walker, the first African American lawyer in Gloucester, travelled to Chicago to meet with Rosenwald and secured funding for six schools and a teacher’s home.

Rosenwald required the community to contribute half of the cost, in money, materials or labor, and he contributed the rest.

The buildings were simple, with each school built east-west or north-south, allowing for optimal sunlight as there was no electricity. The Woodville School was a two teacher, east-west school, with an industrial room on the front of the building and privies to the side.

Only 800 Rosenwald schools are left and, of those built in Gloucester, only the Woodville School remains.

Emancipation Oak

Standing tall near the entrance of the Hampton University campus, with limbs sprawling over 100 feet in diameter, the Emancipation Oak is a lasting symbol heritage and perseverance, and the site of great history.

Its shade served as the first classroom for newly freed men and women looking for an education during the Civil War.

Then, one day in 1863, members of the Virginia Peninsula’s black community gathered to hear their greatest prayer answered as the Emancipation Oak was the site of the first Southern reading of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, declaring “that all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.”

A Memorial to a King

“Virginia, in this critical hour, has the opportunity to give direction and destiny to our troubled South. As Virginia goes, so goes the South, perhaps America, and the world.” -MLK

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. made several visits to Virginia before his assassination.

In 1956 he visited the Hampton Institute. In 1958, he gave a speech on “Facing the Challenge of a New Age” at the First Baptist Church in Newport News. He returned in 1961 to the City Arena in Norfolk to speak to audience of 2,500, and then again in 1962 he addressed an overflowed crowd at First Baptist Church on Scotland Street in Williamsburg.

He would make several more trips, and was even scheduled to come back in March and April 1968 to encourage people in Norfolk, Suffolk and other cities in the Tidewater region to participate in the Poor People’s March on Washington. He cancelled that trip, though, to go to Memphis in support of a sanitation workers’ strike. He was assassinated April 4, 1968 on the balcony of his motel.

The Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Park / Plaza at 25th Street and Jefferson Avenue in Newport News honors the legacy of Dr. King and the trips he made to Virginia, and the message he spread here.

Freedom’s Fortress

Fort Monroe, strategically located at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, sits on a 565-acre peninsula known as Old Point Comfort.

It was the site both of the beginning of slavery in the American colonies, and its end.

In 1619, the first vessel with the first documented Africans enslaved for England’s American colonies arrived at Old Point Comfort before heading up the James River toward Jamestown.

More than 200 years later, slave labor was used to build Fort Monroe, a “Gibraltar of the Chesapeake” constructed to protect the Bay’s inland waters from sea attack.

Thirty years after the fort’s construction was completed, Fort Monroe became a Union territory in Virginia, which would remain a Confederate stronghold through the Civil War.

As such, enslaved men and women made their way to the fort – Freedom’s Fortress.